Not familiar with the project? Start here:

Read Part I | Read Part II | Read Part III | Read Part IV | Read Part V | Read Part VI | Read Part VII

It’s getting more interesting. This definitely describes the last few weeks of the Worthington Cemetery Project. Two different types of information gathering took place. Many community members came out and volunteered their time and energy on both days. This was a great surprise to Jennifer and Taylor from KYK9 Search Dogs. They told us they are generally alone, or accompanied by just five or six community members, during their searches. We had about 30 people present; some stayed the entire time. That is reflective of the Defiance County community. I would like to thank all of them for their continued support of this project.

How it all works

The first step of the KYK9 search was to put large poles in the corners of the area that was to be searched. We have several sources that pointed to a raised spot in the field that was about a half-acre in size. We then used 4-foot-long probing poles to push holes into the soil in a grid, each hole being about two feet apart. This helps aerate the soil and release any scent of human decomposition, which the dogs are very specifically trained to find. One of the ways they are trained is by having the trainers put eight different types of teeth in the ground, only one of which is a human tooth. The dogs must alert to only the human tooth. These dogs have worked on Native American burial locations and afterwards, the trainers were given some of the “sacred soil” to assist in further training. During one job, the dogs located the remains of a missing person whose family donated one of the bones to assist in training the dogs. Jennifer Hall remarked how astounding this was in this family’s worst days to think of helping the dogs to train. But, without these special dogs, the person would not have been found.

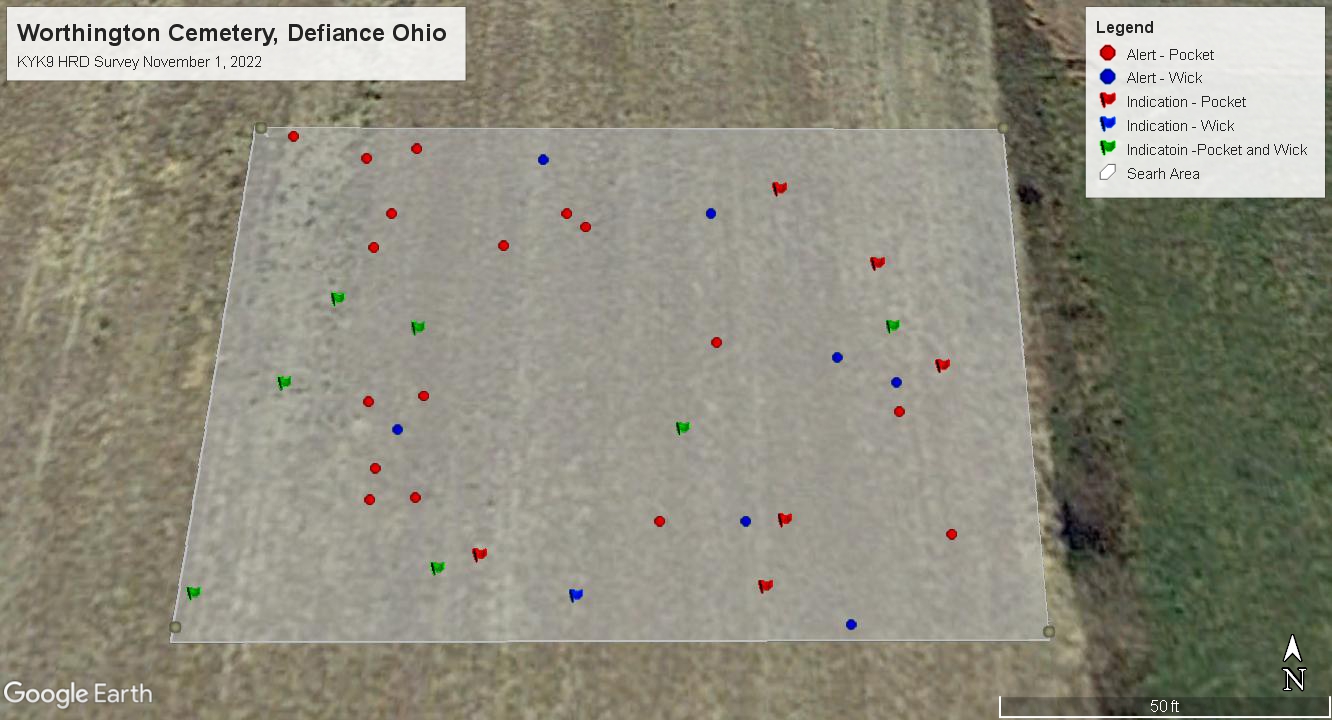

Before the first dog searched, Jennifer explained that the dogs would “alert” to locating the scent of human remains. She said it would be very subtle to the casual observer. The dogs sniff the area, sometimes “stacking” the scent in their nose. This means they take several long, deep sniffs of an area. The dogs then make eye contact with the trainer. Each time they do this, the spot is marked with a small blue flag. She went on to tell us that when they have found the strongest scent, which in the past has proven to be where there are remains, they will lie down. She said they did not expect the dogs to do this at this site.

First up: Pocket!

Pocket was the first of two dogs brought out of the truck to begin the search. Pocket is the older and more experienced of the two, and has worked on numerous searches. She is an 8-year-old Parson Russell Terrier. She was led to the area and immediately began putting her nose to the ground. It was not long before she had alerted, and they began placing flags in the ground. One location really drew her attention; she exhibited the stacking behavior and lay down. Three blue flags were placed on that location to represent a strong indication. They were also labeled with a P for Pocket, as the two dogs would search the same area. She continued to alert and lay down in 4 more locations. Jennifer then led her away from the search area and let her play with a chew toy as a reward for her exertion.

Then came Wick

Wick, a 2-year-old Parson Russell Terrier, was brought out next. He has had the same training as Pocket from the time he was a small puppy. He came out and alerted us to several areas, some the same as Pocket and some that were different. He also lay down on 4 areas that were different from Pocket. All were marked with the blue flags and a W for Wick. It was very impressive, how both dogs were very focused while they were searching for the scent. Taylor then marked each flag location with a GPS coordinate in order to create a map of the area. She is the archaeologist on the KYK9 team, and has seen these dogs find remains, as well as save the lives of missing people. She has also had a lot of experience with graves the same age as these would be.

It is likely that wooden boxes or coffins were used in the burials during this period. The wood would have completely decayed. It is possible that there were burials in cloth or shroud. Any metal such as square nails, hinges, buckles, rings, hair pins, etc. would be with the remains. There could be hair or bits of cloth as well. The soil of the grave shaft, because of being dug up, would be different than the ground surrounding it. It would depend on the height of the grave digger as to how deep the person was buried. Typically, it would have been the shoulder height of that person, so that they could lift themselves out of the grave. Because of erosion and other factors such as farming, the graves would be closer to the surface of the ground now than they were when the bodies were buried.

The view from above

We were able to have Williams Aerial Media come to the field and take some photos and video using a drone. The blue flags are a little difficult to see, but it is better to see the scope of all of the alert locations from above.

Ground-penetrating radar (GPR)

Defiance local Eric Hubbard and his colleague Christopher Lamack, both doctoral students in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, were able to complete a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey of the same area that KYK9 searched. They were representing the Center for Analysis of Archaeological Materials (CAAM), the Penn Museum’s archaeology and teaching labs. Eric and Chris were trained at CAAM, which owns the GPR equipment, and work there in conjunction with their studies. This survey could not have been done without Eric, Christopher, and CAAM. The cost of such a survey made it unaffordable for the library. The KYK9 search was funded by The Friends of Defiance Public Library, Defiance Citizens in Action, and community donors.

The day of the GPR survey was a windy, 32 degree day. It had snowed the night before, but that was mostly gone in the field due to the wind. A few hardy folks were at the field at 8:30am to assist in any way they could. Eric Hubbard and Chris Lamack arrived with all of the equipment. A volunteer had brought his gator to take the equipment out to the location in the field. Once that was loaded, we all headed out. GSSI is a company that sells different types of GPR equipment for those who would like to see them. The team today was using a BridgeScan that could roll along the surface with the GPR sensor as close to the ground as possible. The team could view on the display unit, a small approximately 8” x 10” screen, what was being reflected back into the receiver.

The area to be searched was measured out in meters and each corner was noted with a GPS coordinate. Measuring tapes were left in place and used as guides to keep the lines that the BridgeScan would be pushed down as straight as possible. It was a very precise and professional process to watch. Eric explained to the volunteers how the lines on the screen would change if any object or anomaly in the soil was reflected with the GPR. It does not form an outline of an object, as is seen in movies. That is a huge leap that is taken for entertainment. It is a tedious process to do a complete scan of any size of ground. Once the BridgeScan reached the end of a line, the recording was stopped. Once the device was turned back around 180 degrees, much like a push lawn mower when trying to follow the same lines, the recording was turned back on. The sensor on the ground was about 18” wide. Chris recorded the direction of each pass; in this case, north or south. We started at the easternmost part of the area and ended at the western edge.

Volunteers who were interested were given a chance to walk alongside Eric and watch the radar waves reflected on the screen. We also took some turns pushing the device with Eric, keeping it as straight as possible. I found myself only wanting to watch the screen to view what was beneath the surface. All of these rows of data were being collected by the sensor. We did keep the K9 flags in place. We simply removed them and put them back once the BridgeScan had rolled over that area. These flag locations were also given GPS coordinates by Eric and Chris for their own data collection.

There were over 150 passes made to complete the search area. Eric and Chris explained that it would be beneficial to do a much smaller survey of an area that the dogs did not search but was also still on the raised area in the field. This would compare what is seen in both areas as a control. We helped get that smaller area measured out and it was finished just as the light was beginning to fade for the day. Snowflakes had fallen sporadically throughout the search and people took breaks to get warm and eat lunch. We watched as the team flew a drone above the searched area for detailed photos. The drone was blown around a little bit by the chilly November winds, but was successful in getting the shots. Eric and Chris loaded up the equipment and will work on downloading all of the data into the software. It will create a comprehensive map of what lies in the soil beneath the remnants of soybeans that have long been harvested.

Many community members came both days and witnessed the vastly different searches. Both search teams commented on how wonderful it was to have so much help and interest in the project. This has and continues to be an extraordinary experience for all of us.